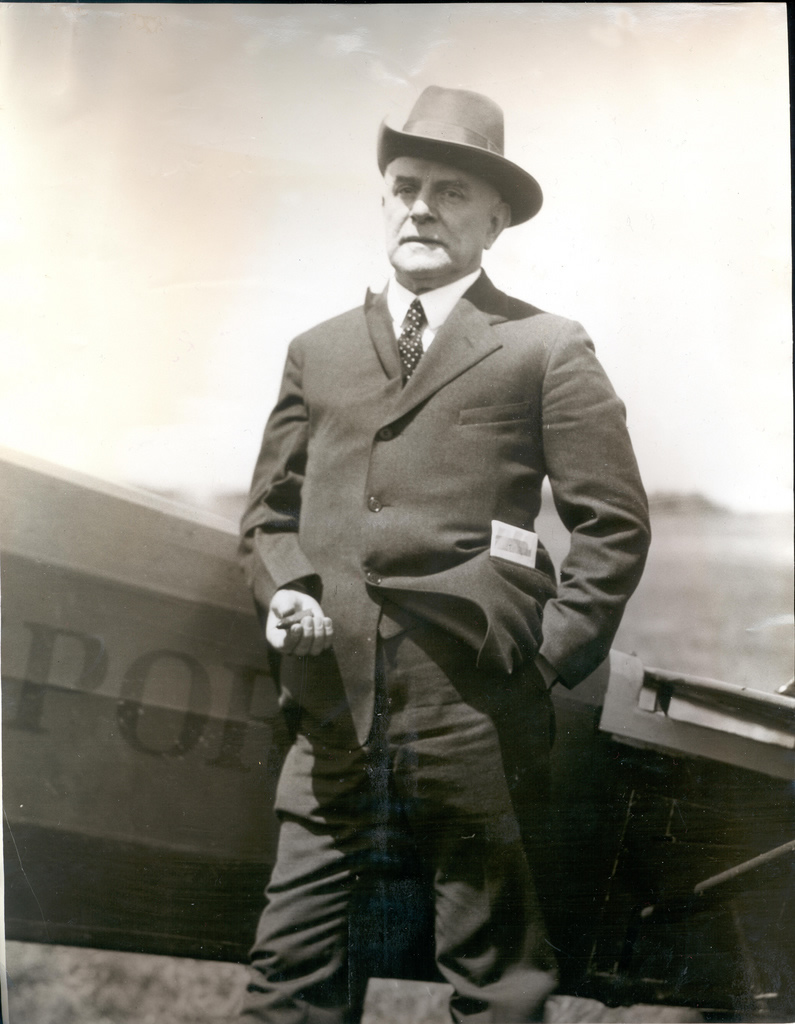

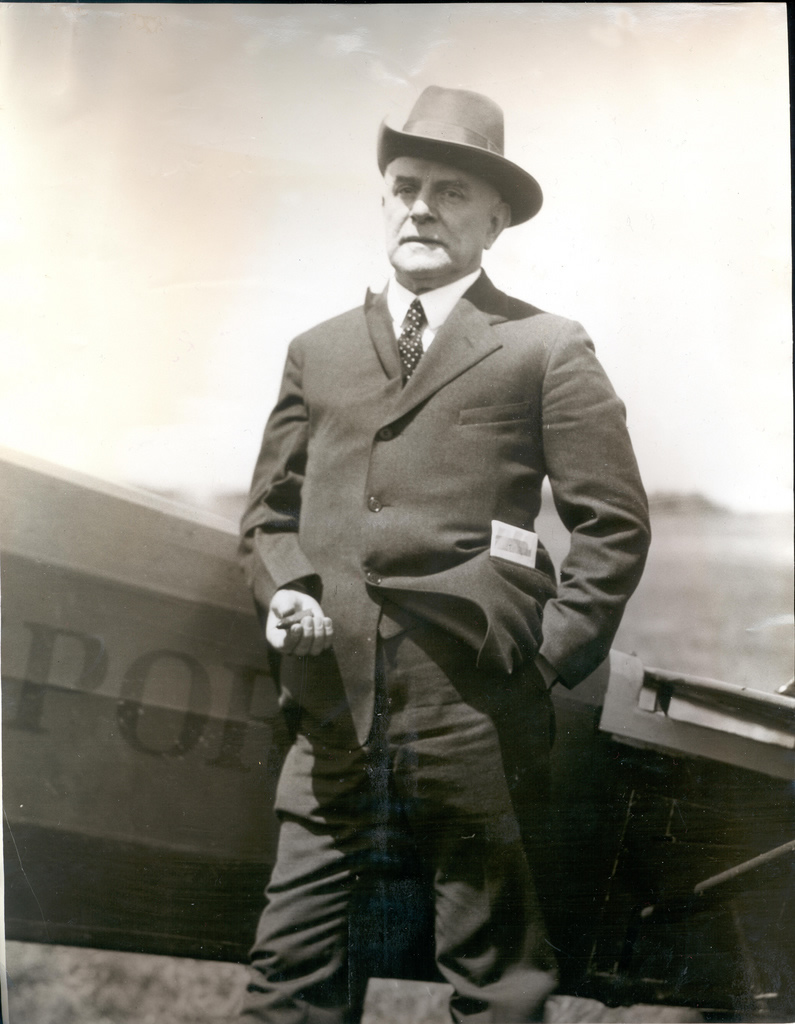

Otto Praeger was the second

assistant postmaster general from 1915-1921 and was in charge of the Post

Office Department's airmail service (1918-1927) during its early years. He

butted heads with the service's first superintendent, Benjamin Lipsner, a fight

that resulted in Lipsner's dismissal from the service. Praeger's hard line

towards the pilots helped set a strike in motion in 1919 after he had ordered

pilots fired for refusing to fly in zero visibility fog. The pilots won public

support during the strike and most were rehired. Praeger turned his stubborn

streak toward Congress, battling for financial support for the service.

National Postal Museum, Curatorial Photographic Collection Photographer:

Unknown.

Otto Praeger was the second

assistant postmaster general from 1915-1921 and was in charge of the Post

Office Department's airmail service (1918-1927) during its early years. He

butted heads with the service's first superintendent, Benjamin Lipsner, a fight

that resulted in Lipsner's dismissal from the service. Praeger's hard line

towards the pilots helped set a strike in motion in 1919 after he had ordered

pilots fired for refusing to fly in zero visibility fog. The pilots won public

support during the strike and most were rehired. Praeger turned his stubborn

streak toward Congress, battling for financial support for the service.

National Postal Museum, Curatorial Photographic Collection Photographer:

Unknown.

NEW

YORK TO BELLEFONTE

Miles

from New York

Zero. Hazelhurst Field. — Long Island,

N.Y.--Follow the tracks of the Long Island Railroad past Belmont Park- race

track, keeping Jamaica on the left. Cross New York over the lower end of

Central Park.

Hazelhurst Field [40.74N / 073.6W] Was created in

1915 as Hempstead Plains Aerodrome, the airfield was taken over the by the Army

and renamed Leighton Hazelhurst (the first NCO killed in

an aviation accident) when the US entered WWI in the spring of 1917. Camp

Albert L. Mills with two airfields, Aviation Field #1 and #2, were created to

train military pilots. Field #1 was renamed Quentin Roosevelt Field in 1918

after Theodore Roosevelt’s son who was killed in air combat during the War.

After the war the field turned over to the US Air Service who relinquished

control in 1920 but the field remained the New York terminus of the airmail

service.

Because of it’s proximity to New York City,

Roosevelt Field was used for most of the aviation events in the early half of

the century including Amelia Earhart, Wiley Post and Charles Lindbergh’s 1927

transatlantic flight. It was closed in 1951 and became the sight of the first

shoping mall built in the US.

1920 Crash of Martan MP 203 (Skyways Journal Magazine)

1920 Crash of Martan MP 203 (Skyways Journal Magazine)

25. Newark, N.J. — Heller

Field is located in Newark and may be

identified as follows: The field is 1-1/4 miles west of the Pasaic River and

lies in the New York, Lake Erie & Western Railroad. The Morris Canal

bound the western edge of the field. The roof of the large steel hanger

is painted an orange color.

25. Orange Mountains. — Cross the Orange Mountains over a small

round lake or pond. Slightly to the right of course will be seen the polo field

and golf course of Essex Country Club About 8 miles to the north is

Mountain Lake, easily seen after crossing the Orange Mountains.

50. Morristown, .J. — About 4 miles north of

course. Identified by group of yellow buildings east of the city. The Delaware,

Lackawanna & Western Railroad pass the eastern side of Morristown.

60. Lake Hopatcong. — A large irregular lake

10 miles north of course

64. Budd Lake. — Large circular body of water

6 miles north of course.

78. Belvidere, N. J. — On the Delaware Rv.

Twelve miles to the north is the Delaware Water Gap and 11 miles to

the south is Easton at the junction of the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers. The

Delaware makes a pronounced U--shaped bend just north of Belvidere. A

railway joins the two ends of the U

111.

Lehighton, Pa. — Directly on course. The Lehigh Valley and

Central Railroad of NJ running parallel pass three miles through

Lehighton. The Lehigh River runs between the railroads at this point. Lehighton

is approximately half way between Hazelhurst and Bellefonte. A fair sized

elliptical race track lies just southwest of town but a larger and better emergency

landing field lies about 100 yards west of the race track. The field is

very long and lies in a north south direction.

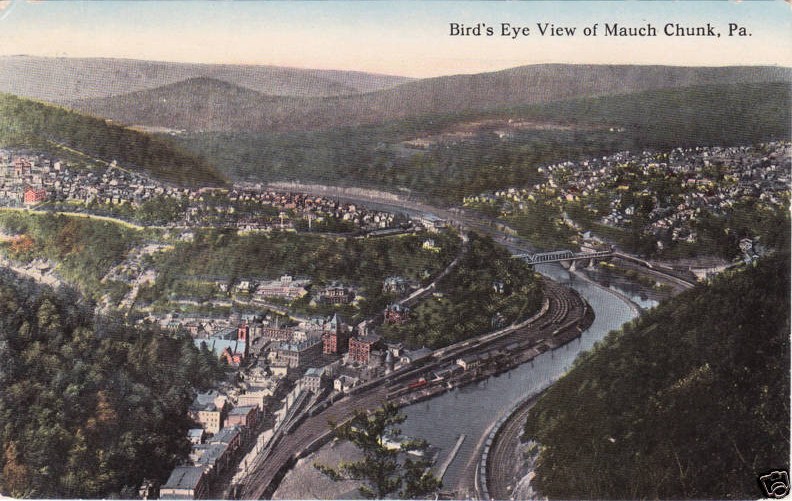

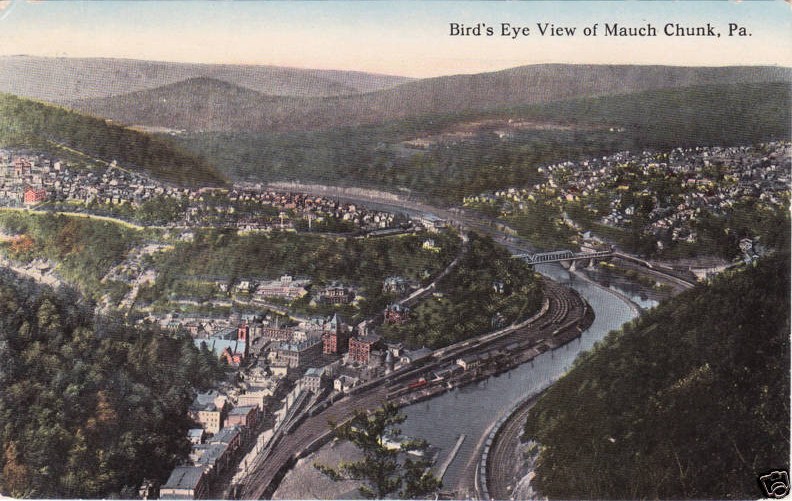

114. Mauch Chunk, Pa.

— Three miles north of Lehighton and on the direct course.

114. Mauch Chunk, Pa.

— Three miles north of Lehighton and on the direct course.

Mauch Chunk PA is now home to the Mauch Chunk

Switchback Gravity Railroad, generally acknowledged as the first roller coaster in the United States. In 1951 The town merged with East Mauch Chunk and renamed

itself Jim Thorpe, PA in hopes of drawing tourists.

121.

Central Railroad of New Jersey. — Two long triangular bodies of water

northwest of the railroad followed by eight or nine small artificial

lakes or ponds about half a mile apart almost parallel with the course but

veering slightly to the south.

148.

Catawissa Mountain Range, which appears to curve in a semicircle about a large

open space of country directly on the course. To the north of the course may be

seen the eastern branch of the Susquehanna. Fly parallel to this until Shamokin

Creek is picked up. This Creek is very black and is paralleled by two

railroads. Shamokin Creek empties into the Susquehanna just below Sunbury.

168.

Sunbury, Pa. — At the junction of the two branches of the Susquehanna

River. The infield of a racetrack on a small island at the junction of two

rivers furnishes a good landing field. The river to the south of Sunbury is

wider than to the north and is filled with numerous small islands. The two

branches to the north have practically no islands. If the river is reached and

Sunbury is not in sight look for islands. If there are none, follow the river

south to Sunbury. If islands are numerous, follow the river north to Sunbury.

170. Lewisburg, Pa. — Two miles west of

Sunbury and 8 miles north.

174 After leaving Sunbury the next landmark

to pick up is Penns Creek. Which empties into the Susquehanna 7 miles south of

Sunbury. Flying directly on course. Penns Creek is reached 6 miles after it

joins the Susquehanna 7 miles south of Sunbury.

178. New

Berlin, Pa. — Identified by covered bridge over Penns Creek.

185. The Pennsylvania Railroad from Lewisburg is

crossed at the point where the range of mountains coming up from the southwest

ends. The highway leaves the railroad here and goes up into Woodward Pass,

directly on the course. A white fire tower may be seen on the crest of the last

mountain to the north on leaving the pass.

202. The next range of mountains is crossed through the

pass at Millheim, a small town. A lone mountain may be seen to the south just

across the Pennsylvania tracks.

217. Bellefonte, Pa.

— After crossing another mountain range with a pass Bellefonte will be

seen against the Bald Eagle Mountain Range. On top of a mountain, just south of

a gap is the Bald Eagle Range at Bellefonte, may be seen a clearing with a

few trees scattered in it. This identifies this gap from others in this range.

The mail field lies just east of town and is marked by a large white circle. A

white line marks the eastern edge of the field where there is a drop of nearly

100 feet.

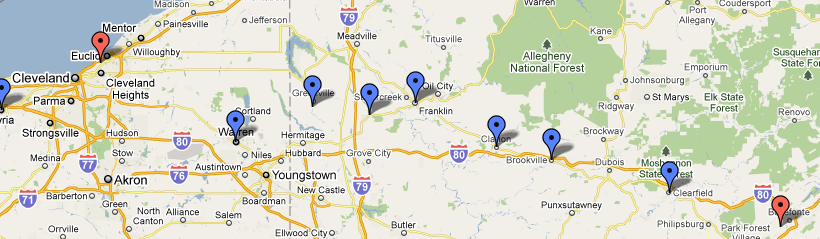

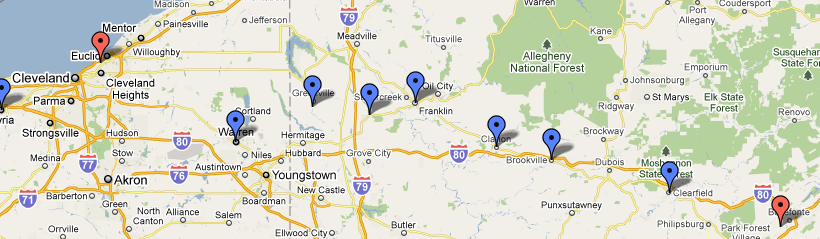

BELLEFONTE

TO CLEVELAND.

Miles from Bellefonte

BEL

+ 0. Bellefonte, Pa. —

Compass course to Cleveland approximately 310. Fly directly toward and over

bare spot on mountaintop south of gap in Bald Eagle Range. First range of

mountains.

BEL + 3. Pennsylvania Railroad,

following course of Bald Eagle Creek.

BEL + 17. New York Central Railroad,

following course of Moshannon Creek.

BEL + 35. Clearfield, Pa. — On west

branch of Susquehanna River. A small racetrack here serves as an emergency

landing field. Two railroads, one from the north and one from the east, enter

Clearfield and both go south from here.

BEL + 55. B. & M. Junction. — One

branch of the Buffalo, Rochelle & Pittsburgh from the east forms a junction

here with the N. & S. line of the Buffalo, Rochelle & Pittsburgh

Railroad. Dubois is 2 miles north of course on the N. & S. line of the

railroad.

BEL + 70. Brookville, Pa. — One mile

north of course, west of city, is 2-mile racetrack, which makes an excellent

emergency field.

BEL + 86. Clarion, Pa. — One mile north

of course. Emergency field marked by white cross and red-brick hangar is here.

The Clarion river passes north edge of city. Railroad from the east ends here

BEL + 110. Franklin, Pa.-Seven miles north of course

at junction of Allegheny River and French Creek. Cross Allegheny River where

there is a pronounced horseshoe bend. This is due south of Franklin.

BEL + 122. Sandy Lake, PA. — Two miles north

of course. Cross the Pennsylvania Railroad at right angles 2 miles south of Sandy

Lake.

BEL + 138. Shenango. — Two miles north of

course. Three railroads enter this town from the north. Two continue south and

one runs east for 3 miles and then turns southeast.

BEL + 152. New York Central Railroad - running north

and south. One mile north of course the Erie crosses the New York Central at right

angles. Four miles west of Erie should be crossed where it turns southward.

Eight miles south of course is Warren with eight railroads radiating out.

BEL + 157. Pennsylvania Railroad, running north and

south.

BEL + 165. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, Running

diagonally northeast-southwest.

BEL + 206. Cleveland

on Lake Erie. — The mail field is in East Cleveland between the two

railroads that follow the lakeshore. The field is near the edge of the city and

near the edge of the freight yards of the New York Central. The field is

distinctly marked by long cinder runway. The airmail hangar is in the southwest

corner of the field. The Martin factory is in the northwest corner of the

field.

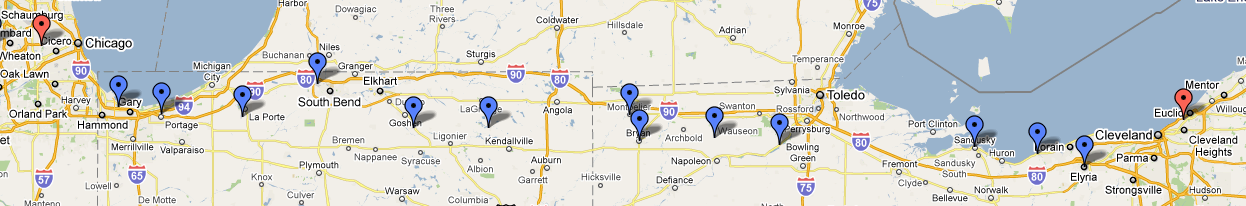

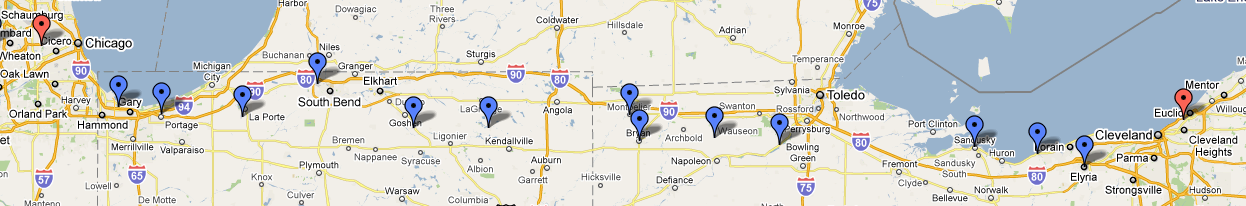

CLEVELAND

TO CHICAGO

Miles from

Cleveland

CLE

+ 0. Martin Field, Cleveland.

— Fly a little west of south for nearly 10 miles or about seven minutes

flying and then due west, thus keeping over good emergency landing fields. The

country between Cleveland and Chicago is divided into sections, section lines

running due north and south and east and west. For the first 15 miles the lake

shore is only a few miles north of the course.

Martin Field - 16800 St. Clair Ave,

Cleveland Ohio. Behind the Glenn L.

Martin Co aircraft plant.

CLE + 20. Elyria,

Ohio. — Five miles south of course. Five railroads radiate out of Elyria.

CLE + 37. Vermilion,

Ohio. — Two miles north of the course. On Lake Erie. The New York Central

Railroad follows the shore line of the lake from Vermilion to Sandusky.

CLE + 55. Sandusky,

Ohio. — Five miles north of the course on Sandusky Bay, a large irregular

body of water crossed by the New York Central Railroad. Continues due west from

this point, following the east-west section lines.

CLE + 112. Maumee

River. — which you cross about 5 miles northeast of Grand Rapids and 5

miles south of Waterville. Waterville is on the east bank of the Maumee and

Grand Rapids is on the south bank of the river where it turns east and

parallels the course for 7 miles.

CLE + 130. Detroit,

Toledo & Ironton Railroad, crossed at right angles. Wausen [Wauseon], Ohio

is 7 miles north of the course and Napoleon is 5 miles south, both on the

above-mentioned railroad. By flying about 11 miles north from the point where

the Maumee River is crossed and then due west the New York Central four-track

railroad will be picked up just before reaching Bryan.

CLE + 152. Bryan,

Ohio is located on the south side of the New York Central tracks, where they

are crossed by the Chicago & North Western and Northern Railroads. Landing

field with hangar and T cinder runway is north of town. Field is two-way, 2,000

feet east and west. Best approach from the east.

CLE + 172. Hamilton

Ohio. — Two miles north of course and 4 miles north of Bryan. On the

extreme south end of irregular-shaped lake. The Wabash Railroad runs to the

south of Hamilton. By keeping the Wabash Railroad in sight for the next 125

miles, you will come in sight of Lake Michigan.

CLE + 196. Walcottville,

Ind. — At the intersection of the Wabash and Grand Rapids & Indiana

Railroads.

CLE + 220. Goshen,

Ind. — Three miles north of course. The Chicago & St. Louis Railroad

is crossed at right angles 3 miles south and 1 mile east of Goshen.

CLE + 243. South

Bend, Ind. — Seven miles north of course. The Chicago & St. Louis

Railroad is crossed at right angles 7 miles south of South Bend.

CLE + 265. La

Porte, Ind. — One mile north of course. The New York Central Railroad

running east from La Porte parallels the course to the lower edge of Lake

Michigan.

CLE + 289. Crisman,

Ind. — Coaling station with large black coal chute north side of track;

has also large race track with course 3 ½ miles north and 1 ½

miles east. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad crosses Wabash at Crisman. Leaving Crisman

fly westerly, following shore of the lake, but keeping about 10 miles from

waters edge to insure safe emergency landing.

CLE + 314. Lake Calumet. — Largest and most

westerly of three lakes. From northern extremity of Lake Calumet fly northwest

on compass course of 315Ż Ashburn Field comes into view to the west and a large

gas reservoir to the east. A large drainage canal will be seen ahead. To your

left, where the Des Plaines River enters the drainage canal, the canal makes a

45Ż turn to the south. Follow the Des Plaines River for about 10 miles and you

will see a large hospital and old race track. This is the speedway and adjoins

the air-mail field on the west.

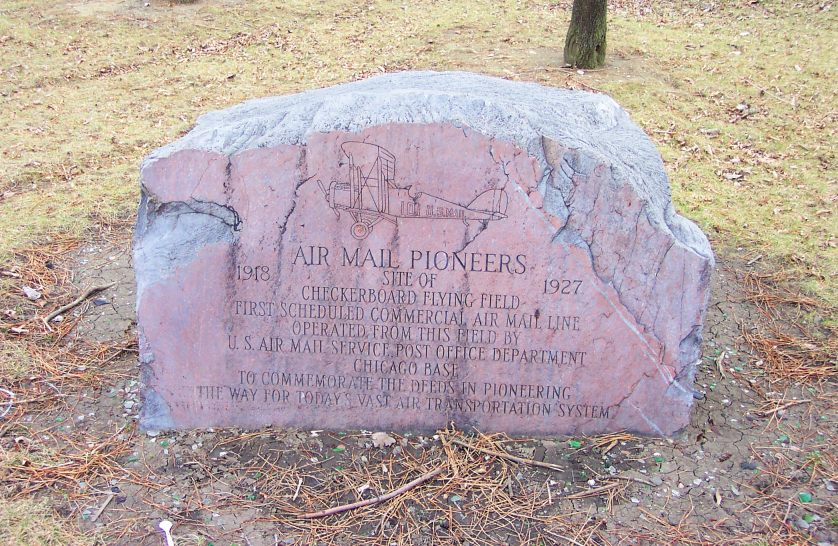

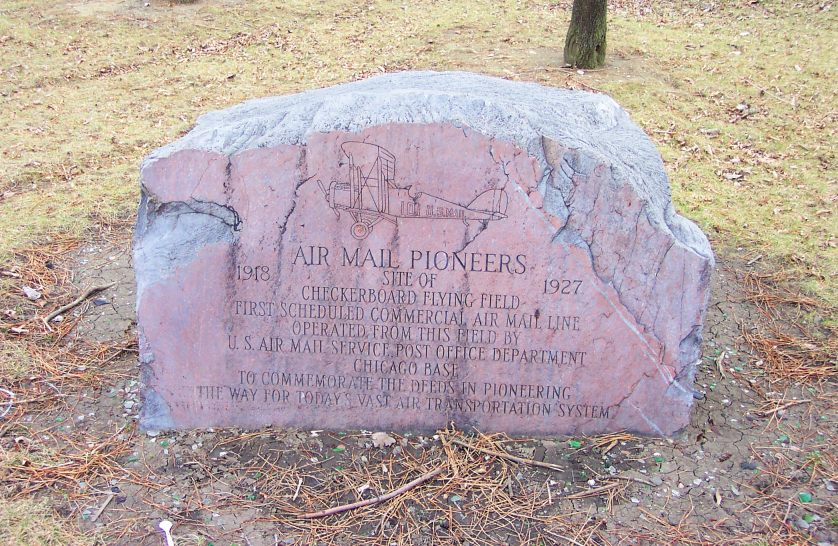

CLE + 330. Chicago

air-mail field or Checkerboard field. — Three large air-mail hangars in

southwest corner of field and private hangar in northeast corner. Four-way

field, but best approach from the south. Telephone and high-tension wires to

west and wires and trees to east of field. Land on large cinder runways.

Sewage-disposal plant with excavations on west side of field. Landing area of

this field large and ample. Telegraph and post-office address of this is

Maywood, Ill. Field is 14 miles west of Chicago post office.

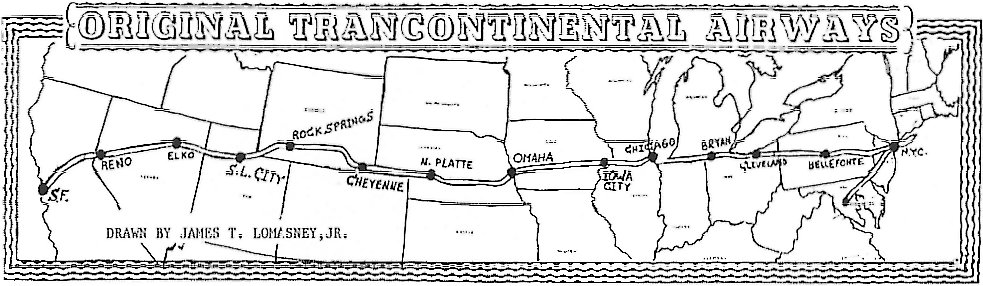

INAUGURALL FLIGHT - FEBRUARY 1922

Four different planes participated in the first

day-night transcontinental flight on February 22, 1922 (George Washington’s

Birthday after the US adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752), two each from

New York and San Francisco.

Of the two New York-based flights, one was forced

down shortly after takeoff and the other landed at Checkerboard, only to be

grounded by a snowstorm.

The first pilot from San Francisco crashed and died

in Nevada but the second made it to North Plane, Nebraska, where a relay pilot

named James H. ("Jack") Knight took over. Knight left North Plane at

7:50PM and arrived at Omaha, Nebraska at 1:15AM, where he found that his relief

pilot had been snowed in Chicago and had never made the flight to meet him at

Omaha. Knight decided to continue on himself and fly the 435 miles to Chicago

despite the fact that the Midwest was getting blasted by the fiercest snowstorm

they'd seen in years.

Since the Des Moines refueling stop was also shut down due to

the weather. Knight was forced to an alternate site in Iowa City which had also

closed down once they had heard that the relay flight from Chicago had been

canceled. Fortunately, the Iowa City night watchman was able to guide Knight to

a safe landing just as the plane's fuel ran dry.

Since the Des Moines refueling stop was also shut down due to

the weather. Knight was forced to an alternate site in Iowa City which had also

closed down once they had heard that the relay flight from Chicago had been

canceled. Fortunately, the Iowa City night watchman was able to guide Knight to

a safe landing just as the plane's fuel ran dry.

While

his plane was being refueled, Knight ate a donut and drank some coffee. He

wasted no time and took off into the driving snow as soon as his plane was

ready; he arrived at Checkerboard at 8:40AM, proving once and for all that

day-night coast-to-coast service was indeed feasible.

James H. ("Jack") Knight

http://www.franzosenbuschheritageproject.org/Histories/Checkerboard%20Field/Checkerboard%20Air%20Field_expanded%20version.htm

CHICAGO

TO IOWA CITY

Miles from Chicago

CHI

+ 0. Maywood, Ill. —

Checkerboard field. Fly directly west, picking up the third railroad to the

north of the field. This is the Chicago & North Western. By keeping on the

section lines and flying directly west this railroad can be kept in sight at

all times until Iowa City is reached. It has white ballast and is

doubled-tracked.

CHI + 14. Wheaton, Ill. — Directly on

course. Town rests in elongated U formed by Chicago & North Western

Railroad. Water tower serves as a landmark.

CHI + 24. Geneva, Ill on the Fox River.

— One mile north of course. Two branches of the Chicago & North

Western cross each other here at right angles.

CHI + 84. Dixon, Ill. — Three miles

north of course on Rock River.

CHI + 96. Twin Cities of Stirling and Rock

Falls. — One on each side of the Rock River.

CHI + 130. Mississippi River. — The

Mississippi River should be crossed about 6 miles below Clinton, Iowa, which is

on the west bank of the Mississippi. Flying in the same direction, the

Wapsipinacan [Wapsipinicon] River will show up soon after crossing the

Mississippi. The Wapsipinacan empties into the Mississippi a few miles south of

the course. Fly in the same general direction with this river in view for 24

miles. The Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific runs in the same general

direction as this river and is never more than 3 miles from it until Dixon,

Iowa, is reached.

CHI + 154. Dixon, Iowa. — One mile north

of the course and 1 mile west of the Wapsipinacan River,

which turns north at this point. Dixon lies between the Chicago, Rock Island

& Pacific and the C. N. W. & St. P., which cross about 1 mile east of

Dixon.

CHI + 173. Tipton, Iowa. — Five miles

north of the course. Soon after Tipton is reached, Cedar Rapids will be

crossed. The Cedar River flows southeast at this point.

CHI + 191. Iowa City, Iowa. — On the

eastern bank of the Iowa River. The Chicago Rock Island & Pacific has four

lines running out of Iowa City. The air-mail field is south of town and on the

western bank of the river. The field is small and is longer east and west.

IOWA

CITY TO OMAHA

Miles from Chicago

CHI + 191. Iowa City, Iowa. — On the

eastern bank of the Iowa River. The Chicago Rock Island & Pacific has four

lines running out of Iowa City. The air-mail field is south of town and on the

western bank of the river. The field is small and is longer east and west.

CHI + 215. Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul

Railway.

CHI + 233. Chicago & North Western

Railway.

CHI + 240. Montezuma. — Directly on

course on Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway.

CHI + 249. Minneapolis & St. Louis

Railway.

CHI + 253. Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway.

— Short line.

CHI + 255. Minneapolis & St. Louis

Railway.

CHI + 271. Monroe. — Slightly south of

course on Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad. Three lines out of this

town.

CHI + 296. Des Moines. — Five miles

north of course. Largest city near course between Iowa City and Omaha. Keep the

Raccoon River in sight until about 18 miles out. From here on keep the Chicago,

Rock Island & Pacific in sight. This railroad follows the direction of the

Raccoon River for this distance. The Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific is 2 to

7 miles north of the course.

CHI + 368. Atlantic, Iowa. — Three miles

north of the course on the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway. At

Atlantic the railroads branch in five directions. If on the course at this

point, that is, 3 miles south of Atlantic, fly nearly due west until Council

Bluffs is seen.

CHI + 413. Council Bluffs, Iowa. — Five

miles east of the Missouri River.

CHI + 418. Missouri River, which is very

irregular in its course and width at this point.

CHI + 424. Omaha, Nebr. — Field is west

of city and can be identified by large hangar with white circle and cross on

roof. North of field is large race track and grandstand. There are two good

approaches, from north and west.

OMAHA

TO NORTH PLATTE

Miles from Omaha

OMA + 0. Omaha, Nebr. — The air mail

field is on the western outskirts of the city, and is 5 miles west of the

Missouri River. The field is rectangular, the long way of the rectangle being

east and west. On the north side of the field is a long grand stand facing

northward and extending east and west. To the north of the grand stand is a

large field with an elliptical race track in it This race track is an excellent

landmark, and the oval may be used for landing if necessary. The west side of

the mail field is bounded by a brook, a few trees, and a railroad track. On the

south the field is bounded by a paved road which ends to the eastward at the

Missouri River. This same road runs due west for several miles beyond the mail

field. On the south side of the field are some high trees and a few telephone

poles. A private hangar is situated across the road from the air mail field

with the word “Airdrome” painted on the roof. The air mail hangar is located in

the southeast corner of the field. The east side of the field is bounded by two

steel wireless towers and a hill covered with high trees. From the northwest is

the best approach, although landings can be made from any direction if made

into the wind.

OMA + 20. The Platte River is crossed at right

angles by flying due west from the Omaha field. By noting section lines the

pilot can determine the correct compass course correcting for drift, as North

Platte and Cheyenne are almost due west of Omaha. For a distance of 70 miles

the Platte River is north of the course never at a greater distance than 10

miles. The Platte River should be crossed between two bridges, one 2 miles

north and the other 2 miles south of the course.

OMA + 21. Yutan. — Directly on the course 1

mile west of the Platte River, 5 lines of railroads form a junction at this

point.

OMA + 33. Wahoo. — A fair-sized town 3 miles

south of the course. Six railroads radiate from Wahoo. An excellent emergency

landing field is located one-half mile south of Wahoo; a smooth barley field

approximately 1 mile long and a quarter of a mile wide. By noting section lines

and flying 25 miles west for each mile south, a direct course may be

maintained.

OMA + 59. David City. — A quarter of a mile

north of the course. Six railroads radiate from this city also.

OMA + 82. Osceola. — Four miles south of the

course. The Union Pacific tracks almost parallel the course from David City to

Osceola, where they turn to the southward. Osceola may be identified by a mile

race track just south of the town.

OMA + 96. The Platte River is crossed again and

runs southwestward. The Union Pacific Railroad is crossed just beyond the

Platte River a half a mile north of the small town of Clarks. Twelve miles

southwest is Central City on the Union Pacific Railroad. This city is 7 miles

south of the course. Central City is directly east of North Platte. If the

pilot passes directly over this city, the east-west section lines can be

followed directly into North Platte. Thirty-five miles southwest of Clarks is

Grand Island in a direct line with Central City. Grand Island is 20 miles south

of the course. At Grand Island there is a commercial flying field where

supplies of oil and gas may be purchased.

OMA + 132. St. Paul, directly on the

course. — Ten miles east of St. Paul one branch of the Chicago,

Burlington & Quincy Railroad runs directly west to St. Paul and lies on the

course. Five railroads radiate out of St. Paul. The Middle Loup River is

crossed 1 mile east of St. Paul.

OMA + 161. Loup City. — Is 5 miles

north of the course on the east bank of Middle Loup River, which is crossed

almost due south of Loup City. The Union Pacific Railroad paralleling the river

is crossed 1 mile east of the river.

OMA + 176. The Chicago, Burlington &

Quincy Railroad tracks following a tiny stream are crossed. The railroad runs

northwest-southeast at this point.

OMA + 183. Mason City. — On the

Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad; is 2 miles north of the course.

OMA + 216. The Union Pacific Railroad,

running northeast-southwest, is crossed midway between Lodi and Oconto; Lodi to

the north and Oconto to the south. A small creek runs through Oconto which

distinguishes it from Lodi.

OMA + 248. North Platte. — After

crossing the Union Pacific Railroad no distinguishing landmarks are available,

but flying west the Platte River will be seen to the south, gradually getting

nearer to the course. The city of North Platte is located at the junction of

the north and south branches of the Platte River. The field is located on the

east bank of the north branch about 2 ½ miles east of the town, just 100

yards south of the Lincoln Highway Bridge. Another bridge, the Union Pacific

Railroad bridge, crosses the stream a mile farther north. The field is

triangular with the hangar at the apex of the triangle and on the bank of the

river. The field, which is bounded on the southwest by the river bank and on

the north side by a ditch, has an excellent turf covered surface always in a

dry condition. The field is longer east and west and the best approach is from

the end away from the hangar. Cross field landings should not be attempted near

the hangar, as the field is narrow at this point. The altitude of North Platte

is 2,800 feet or about 2,000 feet higher than the Omaha field.

NORTH

PLATTE TO CHEYENNE

Miles from Omaha

OMA + 248. North Platte

OMA + 298. Ogallala. — The south

branch of the Platte River parallels the course to this point and the north

branch is only a mile or two north of the course, veering gradually to the

northward. The double tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad follow the course to

this point. Fly directly west from this point, the south branch of the Platte

River and the Union Pacific Railroad, veering to the southward.

OMA + 338. Chappell. — Two miles

south of the course on the Union Pacific tracks and on the north bank of the

Lodgepole Creek.

OMA + 342. Lodgepole. — Directly

on the course between the Union Pacific Railroad and Lodgepole Creek. From here

on to Sidney the course lies over the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and

Lodgepole Creek.

OMA + 360. Sidney. — The Union

Pacific double track runs through here east and west, crossed at right angles

by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad running north and south. Two

miles west of Sidney the Union Pacific double track veers to the north, following

the course of the Lodgepole Creek. The course, due west, lies from 4 to 6 miles

south of the railroad and creek for the next 60 miles.

OMA + 395.

Kimball. — Five miles north of the course on the Union Pacific Railroad

and Lodgepole Creek.

OMA + 420. Pine Bluff, Wyo. — On

the Union Pacific Railroad 2 miles north of the course. The railroad and creek

again cross the course, the railroad, turning westward to Cheyenne and the

creek, continuing south for 4 miles and then eastward. The country between

Sidney and Pine Bluff is the roughest on the whole course from Omaha to

Cheyenne, but plenty of emergency fields are found. A ridge extends southward

from Pine Bluff, on which numerous dark green trees may be seen. Two miles

southwest of Pine Bluff the Union Pacific tracks are crossed and for 5 miles

lie south of the course. Then another intersection of the course and the

railroad looping to the northward and again crossing the course at the small

town of Archer.

OMA + 499. Archer Wyo. — A small town on

the Union Pacific Railroad and 8 miles from Cheyenne.

OMA + 458. Cheyenne

Wyo. — Can be identified by the barracks of Fort Russell. The Cheyenne

field is three-quarters of a mile due north of the town and due north of the

capitol building, whose gilded dome is unmistakable. The field, though rolling,

is very large and landings may be made from any direction. A pilot landing here

for the first time must “watch his step,” as the rarified atmosphere at this

altitude (6,100 feet) makes rough landings the rule rather than the exception.

CHEYENNE

TO ROCK SPRINGS

Miles from Cheyenne

CHE + 0. Cheyenne

Wyo. — Fly west over or to the north of Fort Russell, which is about 4

miles from town, following the Colorado & Southern tracks to the point

where they bend sharply to the north.

CHE + 12. Federal Wyo. — The first town

on the Colorado & Southern Railroad after the railroad makes a sharp bend

to the north. Fly about 6 miles south of Federal and leave the Colorado &

Southern tracks about 1 mile north of the pronounced bend. The compass course,

when there is no cross wind, is about 310Ż. Cross Sherman Hills or Laramie

Mountains at about 9,000 feet above sea level. Crossing this range of mountains

the Laramie Valley appears where landing fields abound.

CHE + 40. Laramie Wyo. — On the Union

Pacific double-tracked railroad. The largest town in the valley. Pass 6 miles

to the north of Laramie.

CHE + 60. Rock River Wyo. — On the

Union Pacific, 20 miles north of the course. The double-tracked Union Pacific

passes through 2 miles of snow sheds at this point.

CHE + 80. Elk MountainWyo. — To the

north of the Medicine Bow Range, a black and white range of mountains, the

black parts of which are forests and the white snow-covered rocks. Elk Mountain

is 12,500 feet high. Fly to the north of this conspicuous mountain over high,

rough country. The Union Pacific tracks will be seen about 15 miles to the

north gradually converging with the course.

CHE + 114. Walcott. — Cross the S. & E.

Railroad 2 miles south of Walcott. The S. & E. joins the Union Pacific at

this point.

CHE + 134. Rawlins Wyo. — Follow the general

direction of the Union Pacific tracks to Rawlins, which is on the Union Pacific

tracks. The country between Walcott and Rawlins is fairly level, but covered

with sage brush, which makes landings dangerous. Rawlins is on the north side

of the Union Pacific tracks at a point about a mile east of where the tracks

cut through a low ridge of hills. Large railroad shops distinguish the town.

The emergency field provided here lies about 1¼ miles northeast of town

at the base of a large hill. Landings are made almost invariably to the

west. Surface of field is fairly good, as the sage brush has been removed.

Easily identified by this, as the surrounding country is covered with sage brush.

Landings can be made in any direction into the wind if care is exercised.

Several ranch buildings and two small black shacks on the eastern side of the

field help distinguish it. Leaving Rawlins follow the Union Pacific tracks to

Creston.

CHE + 159. Creston Wyo. — A small station on

the Union Pacific is the point where the course crosses the Continental Divide.

CHE + 175. Wamsutter, Wyo. — On the Union

Pacific. Fairly good fields are found between Rawlins and a point 60 miles

west. Fields safe to land in show up on account of the absence of sage brush.

The course leaves the railroad where the Union Pacific tracks loop to the

southeast.

CHE + 215. Black Butte. — A huge black hill of

rock south of the course. The Union Pacific Railroad is crossed just before

reaching Black Butte.

CHE + 231. Rock Springs, Wyo. — After passing

Black Butte, Pilot Butte will be seen projecting above and forming a part of

the Table Mountain Range. This butte is of whitish stone. Head directly toward

Pilot Butte and Rock Springs will be passed on the northern side. The field is

in the valley at the foot of Pilot Butte about 4 miles from Rock Springs. It is

triangular in shape, the hangar being located in the apex. The surface of the

field is good. The best approach is from the eastern side.

ROCK

SPRINGS TO SALT LAKE CITY

Miles from Cheyenne

CHE + 231. Rock Springs

CHE + 246. Green River, Wyo. — Follow the

Union Pacific double-tracked railroad from Rock Springs. There is an emergency

field here which is distinguished [on] account of its being the only cleared

space of its size, near the town. Green river is crossed immediately after the

city of Green River is passed. Here the course leaves the railroad which

continues in a northwesterly direction. By flying approximately 230Ż compass

course from here, Cheyenne [Salt Lake City] will be reached.

CHE + 258. Black Fork River. — A very

irregular river, which is crossed at right angles. From Black Fork to Coalville

the Union Pacific tracks are from 5 to 20 miles north of the course.

CHE + 282. Granger, Wyo. — 16 miles north of

the course on the Union Pacific where the Oregon Short Line joins the Union

Pacific from the north.

CHE + 330. Altamont, Wyo. — On the Union

Pacific where the Union Pacific approaches within 6 miles of the course to the

north. The railroad passes through a short tunnel at this point.

CHE + 338. Evanston, Wyo. — After approaching

within 6 miles of the course, the railroad turns sharply to the northwest.

Evanston is on the Union Pacific 18 miles north of the course. There is a good

emergency landing field on the southwest side of Evanston, a mile from the

railroad station. From Evanston the Union Pacific tracks curve toward the

course until Coalville is reached.

CHE + 363. Coalville, Utah. — On the single

track Union Pacific running north and south. The single track Union Pacific

joins the double track 4 miles north of Coalville at Echo City. There is an

emergency landing field here a mile east of the railroad and one-half mile

southeast of town. There is a marker on this field.

CHE + 381. Salt Lake City. — From Coalville

the country is extremely rugged and the pilot should maintain at least 11,000

feet altitude above sea level. The field lies 2 miles west of the city on the

north side of the road or street which extends east-west by the Salt Lake fair

grounds. Locate the fair grounds, identified by an elliptical race track and

large buildings. Follow westward along the road just south of the fair grounds

and the field will be reached 1 ½ miles farther on. The field is about

one-half mile long north and south and landings are usually made in one of

these directions. A landing T is used to indicate the proper place to land.

Elevation here is 4,400 feet. High-tension wires border all sides of the field

except the north.

SALT

LAKE CITY TO RENO

Miles from Salt Lake City

SLC

+ 0. Salt Lake City. —

Fly west from Salt Lake, keeping the two railroads running due west from Salt

Lake to the south.

SLC + 12. Saltair. — Near the salt

works there is an open field which is possible for an emergency landing. The

field lies between the highway and the electric railroad that runs into Salt

Lake City. Is rolling and covered sparsely with sagebrush and should be used

only in case of absolute emergency.

SLC + 14. Antelope Island. — In the

Great Salt Lake, 6 miles north of the course.

SLC + 30. Stansbury Island. — In the

Great Salt Lake. The course crosses this island about 2 miles from its southern

edge.

SLC + 45. The Union Pacific Railroad is

crossed where it runs northeast-southwest. Two miles north of the course the

railroad makes a sharp bend and runs southeast-northwest.

SLC + 50. The Union Pacific Railroad is

crossed again. The Union Pacific continues southeast from here for 10 miles and

then turns westward and parallels the course to Wendover. The course is 6 miles

north of the railroad.

SLC + 98. Salduro. — On the Union

Pacific Railroad, 6 miles south of the course. There is an emergency field here

in vat No. 5, marked by a black T. The vat is circular, 400 feet in diameter

and the bottom, composed of white salt, is hard as a pavement.

SLC + 108. Wendover. — On the Union Pacific, 6

miles south of the course. Opposite the Conley Hotel and the Union Pacific

station there is a landing field L-shaped, 1,200 feet long each way and 600

feet wide, a good emergency field. Four miles west of Wendover the Union

Pacific Railroad turns to the north and east and is crossed 8 miles west of

Wendover. The railroad continues northwestward and reaches a northern point 11

miles from the course. The railroad curves and runs southeast, where it crosses

the Nevada Northern, running north-south at Shafter.

SLC + 130.

Shafter. — At the junction of the Nevada Northern and Western Pacific

Railroads. Opposite the Western Pacific station at Shafter there is a stretch

of ground 1,200 feet wide and unlimited in extent the long way, that may be

used for emergency landings. There is a scattering of sagebrush on this field.

SLC + 145. The

Western Pacific Railroad is crossed, running northwest-southeast, after it

makes a loop to the south just beyond Shafter. The railroad veers to the north

until it is 20 miles north of the course.

SLC + 157. Snow

Water Lake. — An oblong body of water 3 miles south of the course. The

long way of the lake extends parallel to the course.

SLC + 170.

Secret Pass in the East Humboldt Range. — The only pass in this range for

many miles. Some peaks in this range attain an altitude of more than 12,000

feet. The northern extremity of the Ruby Range extending north and south lies a

few miles south of the course and is next seen. Then three branches of

Tamoville Creek flowing north to the east fork of the Humboldt River are

crossed at short intervals. The Southern Pacific and Western Pacific Railroads

follow the course of the east fork of the Humboldt River and gradually converge

on the course where all four join at Elko.

SLC + 204. Elko, Nev. — Lies in the

Humboldt Valley. The air mail field is 1 mile west of the city, with the main

runway east and west. Landings may be made from any direction, although it is

advisable to land east and west. There is a ditch at the east end of the field.

Follow the general direction of the railroad tracks out of Elko, as they run

parallel with the course for several miles.

SLC + 204. Elko, Nev. — Lies in the

Humboldt Valley. The air mail field is 1 mile west of the city, with the main

runway east and west. Landings may be made from any direction, although it is

advisable to land east and west. There is a ditch at the east end of the field.

Follow the general direction of the railroad tracks out of Elko, as they run

parallel with the course for several miles.

SLC + 224.

Carlin, Nev. — Between the Western Pacific and the Southern Pacific

Railroad tracks, 1 mile south of the course.

SLC + 238. Harney. — Six miles south of

the course, midway between the cities of Palisade and Beowawe on the Southern

Pacific and Western Pacific Railroads. South of the railroad tracks here is an

emergency field 1,500 by 900 feet, with a shallow ditch in the center running

across. Landings can be made safely across this ditch. There is a ranch house

in one corner of the field. A narrow gauge railroad runs south from Palisade, a

town 7 miles east of Harney.

SLC + 246. The

course crosses the Western Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroad tracks. Up to

this time the railroad tracks have been on the south of the course, but from

now on the two railroads are to the north.

SLC + 268. Battle Mountain. — At the junction

of the Southern Pacific and the Nevada Central Railroads, 8 miles north of the

course. Battle Mountain lies in a valley surrounded on the east and west by

high ranges. Here will be found an excellent landing field laid out in the form

of an ellipse, marked with a T and a wind-indicator. The field lies directly

west of town. All types of supplies for servicing may be found here. From this

point the railroads turn north and west and leave the course almost at right

angles.

SLC + 278. The

Nevada Central Railroad is crossed 12 miles southwest of Battle Mountain. From

here on for the next 100 miles the course lies over uninhabited and desert

country.

SLC + 293.

Alkali Lake. — Lies on the northern edge of the course.

SLC + 363. Humboldt Lake. — The course

adjoins the southern edge of this lake and crosses the Southern Pacific

Railroad 5 miles beyond. If the pilot elects to not fly the direct course, the

Southern Pacific Railroad may be followed from Battle Mountain to Winnemucca, a

distance of approximately 60 miles. At Winnemucca is an emergency field south

of town, marked by a wind indicator and a T. Supplies necessary for servicing a

ship may be obtained here. At this point the Western Pacific continues on in a

westward direction, while the Southern Pacific turns to the southwest.

Following the Southern Pacific for 30 miles the small town of Imlay will be

reached. There is open unobstructed land on all sides of the town, suitable for

emergency landings. Forty miles farther on will be found the city of Lovelocks.

A first-class landing field is situated here on the eastern edge of the

Southern Pacific tracks just south of town. A permanent T has been placed on

the field and a rolled runway constructed. Gas and oil may be obtained from the

Standard Oil plant on the edge of the filed, and at a near-by fertilizer plant

there is a fully-equipped machine shop which is offered for the use of any

pilot who may need to make repairs to his ship. This field is level and is kept

up in good shape. Pilots coming in must hold the ship up with the gun until

they pass over a series of irrigation ditches at the end of the field. After

these ditches have been passed a landing may be made. Numerous emergency

landing fields may be found all the way between Winnemucca and Lovelocks.

Twenty-five miles farther on the Southern Pacific joins the course 5 miles east

of the southern edge of Humboldt Lake, into which the Humboldt River empties.

To the south of Lake Humboldt is Carson Sink, which has a dry sandy bottom

throughout the year and offers an ideal landing ground, but is uninhabited and

pilots can not receive assistance except along the railroad. By following the

Southern Pacific Railroad from Humboldt Lake southward for 25 miles, Hazen,

Nev., will be reached.

SLC + 388. Hazen, Nev. — Fourteen miles

south of the course on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Four branches of this

railroad radiate out of Hazen. All about the town there are open fields of a

size sufficient to set down an airplane. The best landing field is to the south

and east of the Southern Pacific roundhouse and is a space a mile long and half

a mile wide. Sagebrush grows on the eastern portion of this field and the

southern end is bounded by a set of high-tension wires. A 40-foot T marks the

field. If the pilot has flow as far south as Hazen he can follow the Southern

Pacific westward into Reno. If he is on the direct course, he will cross the

northern branch of the Southern Pacific 7 miles north of where it joins the

east-west main line at Fernley. Twelve miles to the north Pyramid Lake can be

seen.

SLC + 388. Hazen, Nev. — Fourteen miles

south of the course on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Four branches of this

railroad radiate out of Hazen. All about the town there are open fields of a

size sufficient to set down an airplane. The best landing field is to the south

and east of the Southern Pacific roundhouse and is a space a mile long and half

a mile wide. Sagebrush grows on the eastern portion of this field and the

southern end is bounded by a set of high-tension wires. A 40-foot T marks the

field. If the pilot has flow as far south as Hazen he can follow the Southern

Pacific westward into Reno. If he is on the direct course, he will cross the

northern branch of the Southern Pacific 7 miles north of where it joins the

east-west main line at Fernley. Twelve miles to the north Pyramid Lake can be

seen.

SLC + 437. Reno,

Nev. — The air mail field at Reno lies 2 miles west of the city. The main

runway is east and west. The field is marked by a T and wind indicator, and

landing from four ways is unobstructed. Reno is 4,497 feet above sea level.

Whenever possible it is advisable to leave the Reno field on the east-west

runway, taking off to the east. A slight downgrade enables the ship to quickly

obtain flying speed. Just beyond the east edge of the field the ground is

extremely rough and there is a huge ditch here.

RENO TO

SAN FRANCISCO

Miles from Reno

REN

+ 0. Leaving the Reno field

the pilot should head his ship southwest and gain altitude of at least 10,000

feet to pass safely over the Sierras. Practically all of this altitude should

be obtained near the field before starting on the course.

REN + 020. Lake

Tahoe. — The northern edge of Lake Tahoe is 6 miles south of the course.

REN + 025. Truckee.

— On the Southern Pacific near the point where Lake Tahoe Railway joins

the Southern Pacific from the south. Two and a half miles to the northwest of

Truckee lies a very good summertime emergency landing field. All approaches are

clear and a space available for a landing 600 by 2,000 feet. A big boulder

painted white stands on the northwest side of the field and beside it is a

white wind indicator. This field is to be avoided in winter, as snow gathers on

it to a frequent depth of 4 feet. Soon after passing Truckee the Sierras are

crossed. On the direct course 10,000 feet will clear the highest peak, but an

altitude of 15,000 feet should be maintained. The Southern Pacific Railroad

tracks veer to the west and north and from here on to Sacramento are at a

varying distance of 5 to 20 miles north and west of the course.

REN + 065. Colfax. — Seventeen miles northwest

of the course on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Elevation here is 2,422 feet. A

small level field lies one-half mile south of the city. The field should be

used only in an emergency, as it is difficult to get into and during the rainy

season is very soft. The field is 600 by 300 feet.

REN + 085. Shingle Springs. — Seven miles

south and east of the course, on the Placerville Branch of the Southern Pacific

that runs from Placerville to Sacramento. There is a field here one-half mile

west of Shingle Springs, bounded on the north by a highway running to Placerville

and on the south by the Southern Pacific tracks. The field is 1,500 yards long

north and south and 300 yards wide east and west. The ground is level, hard,

and smooth. The elevation here is approximately 1,000 feet.

REN + 095. The Southern Pacific, running from Placerville

to Sacramento, is crossed at right angles 1 mile southeast of where it makes a

right-angular bend and approximately parallels the course for the next 15

miles. The course lies from 1 to 3 miles southeast of this track.

REN + 0112. Mather Field. — Is the

Army Air Service station in the Sacramento Valley, equipped like all Air

Service flying fields. It is located to the east of Sacramento and near the

small siding called Mills, 2 miles north and east of the course. A huge white

water tower serves as an excellent landmark as well as the three lines of

buildings on the ground. Three railroads are crossed in a stretch of less than

10 miles soon after leaving Mather Field. The Southern Pacific Railroad is to

the northeast of the course at a varying distance of 10 to 15 miles after

leaving Mather Field. Southwest of the course the Sacramento River will be seen

soon after crossing the three railroad tracks at a distance of 5 to 10 miles.

REN + 0152. Suison [Suisun] Bay. —

Into which the Sacramento River empties, a large oblong body of water parallel

to the course. The pilot will fly along the southwest side of this bay.

REN + 0162. Martinez. — On the

southeast corner of Suison bay. One mile northwest of the course.

REN + 0177. Durant Field, Oakland, Calif.

— On the eastern side of San Francisco Bay. The field runs almost due

east and west and has a hangar, wind indicator, and T laid out on it. By coming

in from the east over the hangar an unobstructed run of about 2,000 feet is

obtained. North and south the field is rather narrow and somewhat rough. All

supplies necessary for reservicing a ship may be obtained here. From here fly

directly across San Francisco Bay. The course goes directly over Alcatraz

Isla nd, covered with white Government buildings. Goat Island, larger than

Alcatraz, and more irregularly shaped, on which is located the Naval Station to

be seen to the south.

nd, covered with white Government buildings. Goat Island, larger than

Alcatraz, and more irregularly shaped, on which is located the Naval Station to

be seen to the south.

REN + 0187. Marina Field. — Is

stationed on the south of San Francisco Bay, 3 miles from the Golden Gate, on

the east portion of the old fair grounds. It can be identified by the Palace of

Fine Arts Building, which has a large dome roof, at the west end of the field; a

monument 150 feet high, the Column of Progress, is on the north side of the

field. The city of San Francisco is to the south. There is a prevailing

southwest wind here. A double line of wires borders the eastern edge of the

field and this, in conjunction with the gas plant in the same vicinity, force

the pilot to come in high. The pilot should hold the ship off until the runway

is reached coming in either direction, as both the east and west edges of the

field are very rough. Landings should not be attempted from any direction other

than the east and west.

The Post Office Flies the Mail, 1918-1924

The Post Office Flies the Mail, 1918-1924

On August 12,

1918, the Post Office Department took over airmail service from the U.S. Army

Air Service (USAAS). Assistant Postmaster General Otto Praeger appointed

Benjamin B. Lipsner, who left the USAAS, to head the civilian-operated Air Mail

Service. He would remain only until December 6, when he resigned over what he

felt were wasteful and “unnecessary expenditures.” One of Lipsner's first acts

was to hire four pilots, each with at least 1,000 hours flying experience,

paying them an average of $4,000 per year. The department also abandoned the

polo grounds in Washington, D.C., and moved north to the larger airfield at

College Park, Maryland, where it would begin its route to Philadelphia.

The department

used mostly World War I surplus de Havilland DH-4 aircraft, which were

flimsy and not designed for long cross-country flights. Another popular plane

was the Standard Aircraft Company JR-1B, which could carry 300 pounds (136

kilograms) of mail as well as 60 gallons (227 liters) of fuel. During 1918,

including the initial four pilots, the Post Office hired 40 pilots, and by

1920, they had delivered 49 million letters. In its first year of operation,

the Post Office completed 1,208 airmail flights with 90 forced landings. Of

those, 53 were due to weather and 37 to engine failure. The Post Office also

bought the German-made Junkers F 13, which it renamed the

J.L.6 after John Larsen, who had imported it to the United States. The postal

service had high hopes for this all-metal plane, but it proved ex tremely

dangerous and was removed from service after several pilots were killed in

fiery crashes.

tremely

dangerous and was removed from service after several pilots were killed in

fiery crashes.

Postal aircraft

could fly with sacks of mail for an average cost of $64.80 for each hour in the

air. Pilots received a base pay of about $3,600 per year and then were paid

five to seven cents more for each mile they flew, flying an average of five to

six hours each day. After a year in operation, postal revenues for the year

totaled $162,000. The cost to fly the mail had been just $143,000. This first

year of operation was to be the only time in airmail history that the service

showed a profit.

The largest

airmailcustomers were in the banking business. They used the service to send

checks and financial papers more quickly. Bankers wanted to reduce the float

time of checks and pushed for an extension of routes. Financial papers were

light, and the cost to send them was low—just 16 cents an ounce, having

been reduced from 24 cents in July 1918 to attract more customers. It was

further reduced to six cents per ounce on December 15, in an effort to draw

even more customers. In July 1919, the extra charge for airmail was eliminated

completely and airplanes began to carry a random selection of mail. The charge

would be reinstated in 1924 when regular transcontinental service began.

International

airmail delivery began on March 3, 1919, when Bill Boeing and Eddie Hubbard carried

60 letters from Vancouver, Canada, to Seattle, Washington, in a Boeing Model C.

Later that year, Hubbard began flying a Boeing B-1 flying boat for airmail

delivery between Seattle and Victoria, British Columbia. He would continue

flying the plane for eight years—amassing more than 350,000 miles

(563,270 kilometers).

Flying conditions

were poor, and the pilots were forced to fly in all kinds of weather. Praeger,

who didn't know how to fly, was unyielding about keeping the mail on schedule

in spite of the risk, hoping that it would make the public trust the service more.

Tragically, of the 40 pilots hired when the Post Office took over airmail

operations, at least half had died by 1920, most from weather-related crashes.

In July 1919,

pilot Leon Smith refused to fly the mail from New York to Washington, D.C.,

because of rain, clouds, and visibility of only 200 feet (61 meters). Praeger

ordered him to make the trip anyway, using only his magnetic compass to

navigate. Smith and his fellow pilot E. Hamilton “Ham” Lee refused to fly in

the dangerous weather. Both pilots were fired and then, all the pilots in the

airmail system went on strike. After three days of talks, the pilots and

managers agreed to require field managers to make a flight check in bad

weather. The field managers could either fly the inspection themselves or if

they were not pilots, could sit in the mail bin in front of the pilot. The

flight would continue only if the field manager said weather conditions were

safe for flying.

Postal planes

began flying across the country on September 8, 1920. But these flights took

place only in daylight because pilots relied on visual landmarks to navigate.

Each night, the mail would be loaded onto railcars and would travel overnight

until daylight allowed another plane to take over. Rugged terrain and poor

weather, especially in the West, combined with unreliable planes to slow the

service. The service was criticized for being uneconomical and unsafe. Praeger

decided to demonstrate how far airmail had come by flying across the country by

day and by night. On February 22, 1921, pilot Jack Knight helped to change the mix

of railroads and aircraft and give airmail service more status during a test of

transcontinental airmail.

As part of a relay

team of pilots from San Francisco to New York, Knight was scheduled to carry

the mail only part of the way, but a snowstorm in Chicago delayed all the other

pilots. Knight flew the mail from North Platte, Nebraska, all the way to

Chicago, though normally other pilots waiting at stations would have split the

trip. Much of Knight's flying was by night in the bitter cold. He found his way

by looking for bonfires and flares lit by helpers on the

ground. After 830 miles (1328 kilometers), Knight finally connected with his

relief pilot in Chicago. When the last man in the relay reached New York, the

total time to carry the mail had been 33 hours 20 minutes—compared to

four and a half days by train. This was Praeger's final triumph before he was

replaced in April when the administration changed.

Progress continued

to be made. By November 1921, 10 radio stations were installed along the New

York-San Francisco routes to transmit weather forecasts. Soon, parachute flares

were installed in the undercarriage of aircraft to light emergency fields.

Flashing beacon lamps or searchlights were mounted on towers all across the

United States 10 to 30 miles (16 to 48 kilometers) apart depending on the

terrain. Most pilots still flew about 200 to 500 feet (60 to 152 meters) above

ground level so they could navigate by roads and railways. By the end of 1921,

98 airmail planes were in service. In 1922, Tex Marshall helped form the Air

Mail Pilots Association and became its president. On July 16, 1922, the Air

Mail Service could brag that it had completed one year of flying without a

fatal accident. In February 1923, the service was awarded the Collier Trophy for its achievements.

Regularly

scheduled transcontinental service began on July 1, 1924, using pilots leaving

from both the East and West coasts. The pilots also began regular night

flights. They were guided by a lighted transcontinental airway with rotating

beacons and brightly lit emergency landing fields along the way, and they timed

their night flying so as to reach the end of the lighted airway by daybreak.

They tested the new gyroscopic needle to indicate whether

aircraft wings were level and altimeters to show if the aircraft

was climbing or descending. The Post Office resumed using special airmail

postage, which it had discontinued in 1919. Airmail now cost eight cents to

travel in any of the three zones comprising the transcontinental route and

could travel all across the country for 24 cents. By the end of 1924, airmail

planes were routinely completing the New York to San Francisco route within 34

hours.

Sources:

Bruns, James H. Mail on the Move. Polo, Illinois:

Transportation Trails, 1992.

___________. Turk Bird--The High-Flying Life and

Times of Eddie Gardner. National Postal Museum, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian

Institution Press, 1998.

Chaikin, Andrew. Air and Space--The National Air

and Space Museum Story of Flight. Boston: Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown and

Company, 1997.

Christy, Joe, Wells, Alexander T. American

Aviation--An Illustrated History. Blue Ridge Summit, Pa.: Tab Books Inc., 1987.

Ethell, Jeffrey L. Smithsonian Frontiers of Flight.

Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, New York: Orion Books, 1992.

Jackson, Donald Dale. Flying the Mail. Alexandria,

Va.: Time-Life Books, 1982.

Leary, William M. Aerial Pioneers – The U.S.

Air Mail Service, 1918-1927. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press,

1985.

Smith, Henry Ladd. Airways: The History of Commercial

Aviation in the United States. New York: Russell & Russell, Inc. 1965.

Further Reading:

Boughner, Fred. Airmail Antics. Sidney,

Ohio: Amos Press Inc., 1988.

Heppenheimer, T.A. Turbulent Skies; The History

of Commercial Aviation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1995.

Holmes, Donald B. Airmail, An illustrated

History 1793-1981. New York: Clarkson N. Potter Inc., 1981.

Lipsner, Benjamin B. The Airmail Jennies to Jets.

As told to Leonard Finley Hiltsd. Chicago: Illinois, Wilcox and Follett

Company, 1951.

Shamburger, Page. Tracks Across the Sky. New York:

J.B. Lippincott Company, 1964.

http://www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Government_Role/1918-1924/POL3G8.htm

nd, covered with white Government buildings. Goat Island, larger than

Alcatraz, and more irregularly shaped, on which is located the Naval Station to

be seen to the south.

nd, covered with white Government buildings. Goat Island, larger than

Alcatraz, and more irregularly shaped, on which is located the Naval Station to

be seen to the south. The Post Office Flies the Mail, 1918-1924

The Post Office Flies the Mail, 1918-1924  tremely

dangerous and was removed from service after several pilots were killed in

fiery crashes.

tremely

dangerous and was removed from service after several pilots were killed in

fiery crashes.